There is a sense amongst the young British electorate that they are powerless in affecting change in politics, especially through their vote. However, Toby Whelton, IF researcher, argues that while the odds may be stacked against them, there is still real potential for the young to shape the upcoming election.

Voter turnout is low but lowest for the young

A recent report from the British Social Attitude Survey has shown a decline in British people’s engagement with politics over the last decade. This has been reflected in voter turnout decreasing from 66% in 2015 to 61% in 2019.

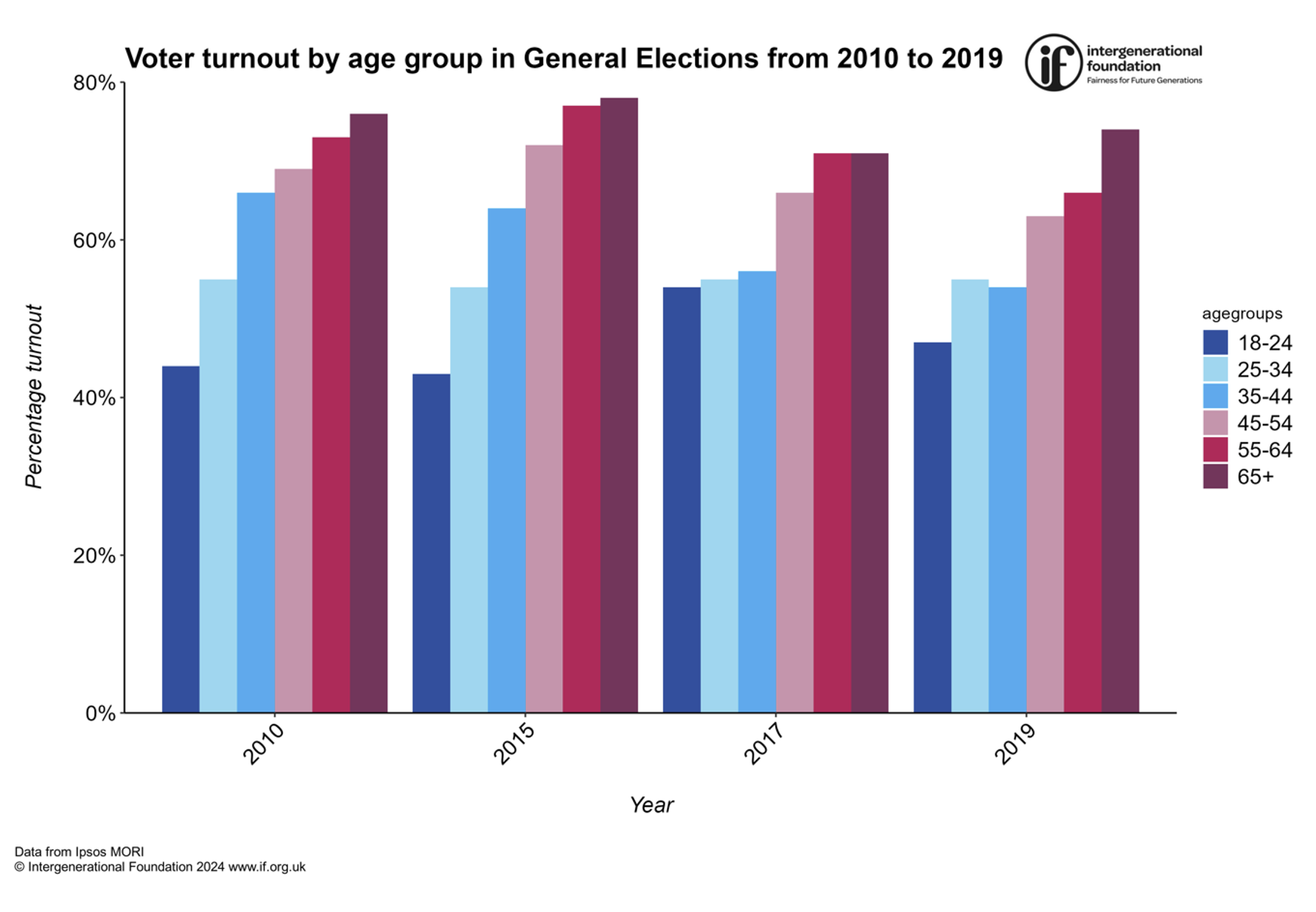

However, not all parts of British society are equally disillusioned with politics. The young are by far the most disengaged group, with voter turnout amongst the young considerably lower than any other age group. In the 2019 general election, 47% of 18–25 year-olds voted compared to 74% of those aged 65 and above.

Why in Britain?

A gulf in participation between the young and the old in our democracy is not a given. Between 2002 to 2016, youth participation in national elections in the UK was 27 points below the average of the eight large EU15 states. British 18–24 year-olds were half as likely to vote than their Swedish counterparts. Britain’s young turnout record is uniquely poor.

It is hardly surprising young people in Britain are fed up with politics. Years of intergenerationally unfair policies have disillusioned young voters. The young collectively face billions of pounds of student debt, a housing crisis, a mental health crisis and a climate emergency, all of which policymakers collectively ignore in favour of pandering to the grey vote by maintaining the triple lock on the state pension and an unequal tax system that takes more from the young than the old.

This is not to say young British people do not care about politics. Student protests, online activism and social media campaigns all show the young want to play an active role in shaping the future of the country. It is not so much a disillusionment with politics, but a disillusionment with political institutions. The young believe the British political class do not have the young’s best interests at heart and unfortunately they are often proved right.

Political math

The grey vote’s disproportionate political power goes beyond voter participation. Baby-boomers simply constitute a far broader part of the population than any other demographic. There are over 21 million people living in the UK aged 55 and over, compared to 13.3 million 18 to 35 year-olds.

When this imbalance is combined with older generations far greater turnout, the young vote is dwarfed. In 2019, 18–35 year-olds had roughly 4.8 million collective votes, while those aged 56 and over had 15.6 million – over triple the amount. Ultimately, there are more votes to be gained by pursuing policies that benefit the old, even if at the expense of the young.

The grey bloc

While the old vote as a bloc to protect their group interests, the same cannot be said for the young. The young are typically driven by issues (albeit valid issues), whether it be climate, foreign wars or tuition fees, as opposed to the broader interests of the group at large. Many can be characterised as ‘stand-by’ citizens, who only vote when prompted by particular concerns.

This has meant that while no politician dare oppose the state pension triple lock at the risk of losing the vote of an entire demographic, politicians have faced little consequence for repeatedly betraying the interests of the young.

Young turnout still matters

However, this electoral imbalance at the heart of British politics does not validate young people’s decision to not vote. Rather, it becomes even more imperative that young people vote, hold the government accountable and stand up for their interests.

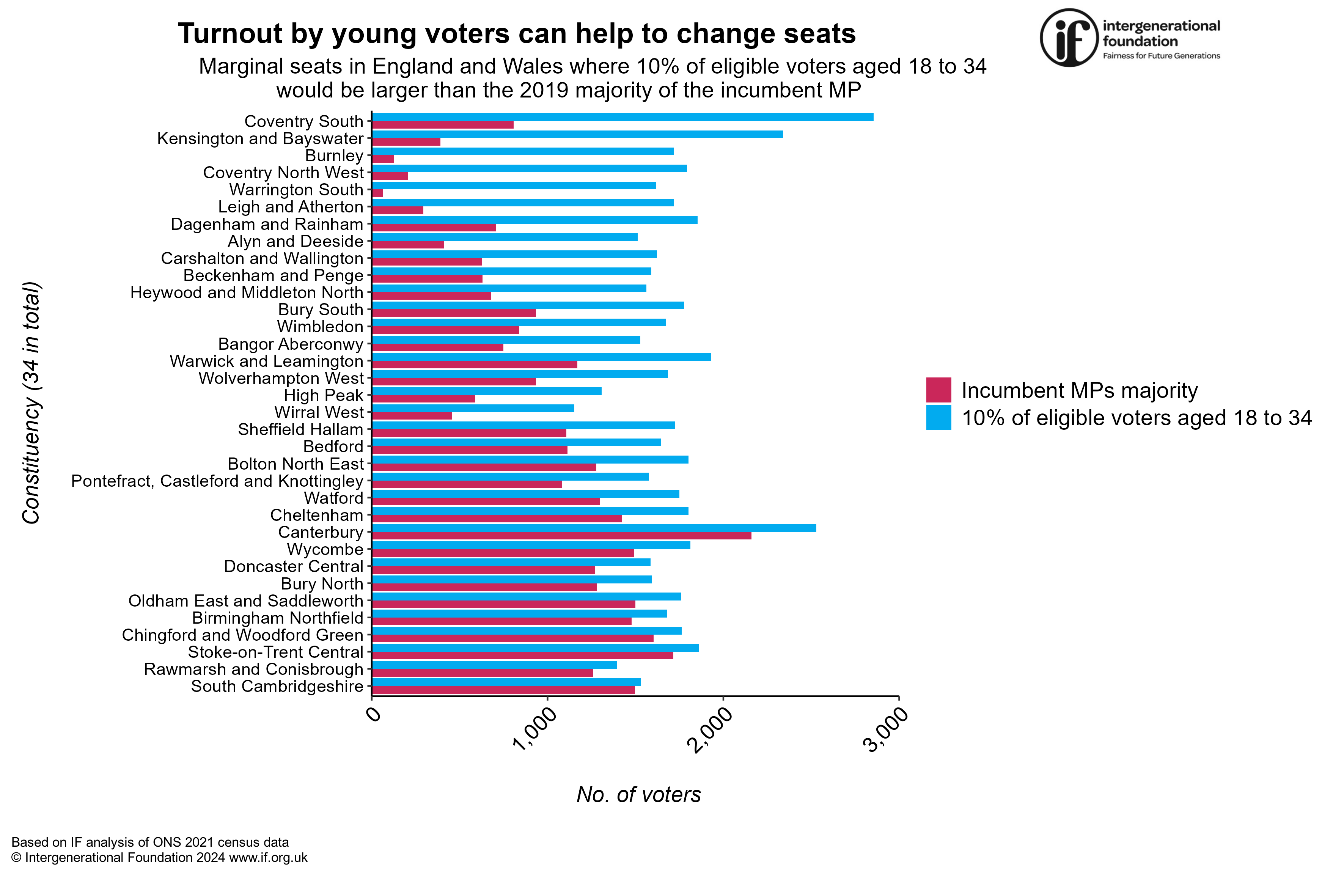

IF analysis has revealed the considerable impact an uptick in youth turnout would cause. There are thirty-four constituencies where a 10% increase in turnout from eligible youth voters is greater than the incumbent MPs 2019 majority. In other words, there are thirty-four marginal constituencies where the result could be determined by young voters alone. This is up 20 points from the 2017 election. The young still have the chance to have a say in this election, but only if they vote.

Register, register, register

Underlying the problem of turnout, is the problem of registration. As of 2022, only 66% of 18–34 year-olds are registered to vote, compared to 96% of individuals aged over 65. Young people are in particular need of reminding to register as they are often more mobile, tending to move houses more as students and then by renting.

The deadline to register is Tuesday 18 June. Up until then, make sure you register yourself, tell your friends and family to register, tell colleagues to register, tell the cashier to register. Do everything possible to make sure all are registered. Only if more young people register and turnout to vote, will politicians be forced to address the systemic and intergenerationally unfair issues facing the young that have been ignored for decades.

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate.